On Aug. 7 and again Aug. 9, pockets of powerful thunderstorms rolled across Atlantic Canada.

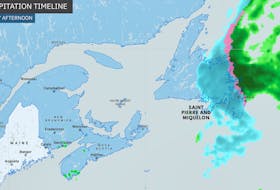

Severe thunderstorms developed and watches and warnings were issued, off and on, all week. Some areas did get very heavy weather with flooding rains and damaging winds, while those who live along a south-facing coastline watched as the storms petered out before reaching them.

Thunderstorms need two things to survive: unstable air and some type of lift –usually a frontal boundary. It just so happens parts of Atlantic Canada are lacking in both departments when it comes to a typical cold-front-driven thunderstorm situation.

The biggest reason for this is a relatively dense, more stable layer of air called a “marine layer.” A marine layer happens where the ocean cools off the air directly above it, making it denser, and keeping it below the warmer air on top. That setup is not conducive to thunderstorm growth.

When a cold front approaches from the northwest, coastal Nova Scotia and Newfoundland will experience south winds, which brings the “marine layer” inland. When the thunderstorms eventually hit this more stable air, they typically weaken.

- Read more Weather University columns.

- Have a weather question, photo or drawing to share with Cindy Day? Email [email protected]

Cindy Day is the chief meteorologist for SaltWire Network.