The oddest hunter in our forests is not a big wolf or an insect-eating plant, but of all things a fungus — one that traps tiny worm-like animals underground and sucks the nutrients out of them.

But there’s more to our many fungi (that’s the plural) than this eyebrow-raising behaviour that some of them use. They also help forests grow, and this relatively new area of knowledge is just exploding today.

More on that part in a moment.

For starters, a fungus is not a plant, and it doesn’t matter how much a mushroom may look like one. There are plants, there are animals, and there are fungi, and these are all different.

On top of that, the mushroom isn’t the whole fungus. Most of the fungus is a net of fine threads stretching all through the soil and inside rotting logs, covering maybe 100 square metres, and the mushroom is just the part that reproduces by making spores. It’s like the flower on a tree.

Fungi also include yeast and moulds.

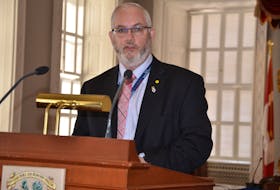

“People have no idea that when you go to a forest, it’s interwoven by fungi,” says Paul Keddy, a retired University of Ottawa biologist who lives in the forest of Lanark County. “And you don’t know where they are except when you see a mushroom, and that is one that is trying to reproduce.”

Each fungus needs food. And like all living things, this includes nitrogen. Keddy again: “Nearly every amino acid, the basic units for constructing protein, has a nitrogen molecule. So you can’t build a fungus or a deer (or a human) without that essential building block.”

But nitrogen is in limited supply. So some fungi — including some where we live — have evolved the ability to loop their threads around tiny animals called nematodes, like a noose. Soil nematodes are worm-like creatures that are a millimetre long, or less. The soil is full of them.

If the fungus can trap them with a loop of its body, or with a sticky bump on its thread like flypaper, it can then eat the nematode. Keddy writes in his 2017 book Plant Ecology : “A short digression on nematodes: although this habit of consuming nematodes may seem unusual, nematodes are actually one of the most abundant groups of invertebrates in the biosphere, and are present in a wide array of natural habitats, particularly soil, where they live in thin water films and feed mainly on fungi and bacteria; 100 g (grams) of soil may yield 3,000 nematodes. There are more than a 150 species of fungi that kill nematodes.”

“What they’re after with the nematodes primarily is raw materials” that help the fungus grow, he said. He compares it to a pitcher plant, which traps and dissolves insects.

Some fungi set out their traps when they sense nematode pheromones.

But the fungus story is bigger than this.

“Fungi are actually turning out to be utterly essential for all our native forests. None of our trees apparently can properly grow without the fungi that are attached to their roots,” Keddy said.

The fungus helps tree roots absorb nutrients and water, and has side benefits including protection against disease. In return, the fungus receives energy that the tree gets from sunlight.

“Which means that when we look at a tree, it’s not really an individual. It is alive only because it’s paired with a fungus.”

If a researcher puts a drop of radioactive material in the ground, it can be tracked moving through this complex network of ground and trees just like a medical radioisotope inside the human body.

“So a forest is no longer seen as individual trees, but as a network of trees connected underground by fungi,” he said. This even means that different tree species are linked.

Some fungi help many tree species. Others have a favourite tree, “which is why if you are looking for certain kinds of mushrooms, you look under certain trees.”

“Canada has an economy based on forestry. Traditionally how do we train foresters? We train them about trees, and about insects that eat the trees,” Keddy said.

“You could argue that the Canadian forest industry is, in fact, depending on the health of beneficial fungi, and we know very little about them. You could argue our forestry departments should be far more focused on soil fungi and how they are connected to trees.”

A side note: Planting a tree only works if it has this invisible, underground support system, he says. “And some of our urban trees may be struggling for lack of that.”

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2019