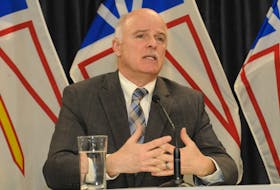

But Dean Peckford believes that they can do even more.

Peckford has been a member of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary for over 21 years and to his knowledge is the first officer to be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Over the course of 10 years, that disorder, coupled with anxiety and depression, has for lengthy periods of time prevented Peckford from being able to work.

He shared his story with a group of nearly 100 people at the Greenwood Inn and Suites on Thursday. Firefighters, police officers, emergency responders, educators and people with an involvement in community mental health attended a “Let’s Talk” Mental Health Week event sponsored the Canadian Mental Health Association — Newfoundland and Labrador Division, the Rotary Club of Corner Brook and BellAliant.

Peckford has been back on the job for over a year now, but no longer walks a beat or investigates major crimes. He’s now in an administrative position.

Peckford joined the RNC in St. John’s in November 1990.

He can’t say his disorder was triggered by one event as there a several that seem to be significant.

In 1995 Peckford started to question his career choice. Around the same time he was encountering some issues in his personal life and he and his wife decided to move to Corner Brook. They were both from here and decided to give living here again a try.

In the fall of 1996 Peckford moved into the criminal investigation division and after a couple of years of working on cases of child abuse and robberies decided that was not for him. In early 1998 he applied to go back on street patrol, but a homicide in the city delayed that move.

The victim was a six-week-old baby and, with his own wife pregnant at the time, the investigation took a big toll on him.

But he didn’t think of his mental health or of “taking care of Dean.”

After that he was called out to a motor vehicle accident in which a man, someone he knew, had died. The man had a dog with him that was injured and when the veterinarian said the dog would have to be put down Peckford broke down and cried. By the following week he was put off work for three months.

By the fall of 2000 Peckford was back on street patrol and an incident occurred that, though he wasn’t a part of it, significantly changed his life.

Another member had discharged his firearm and a person was dead because of it. Peckford was supposed to have worked that night, but opted to take it off.

In the days and months that followed he felt extreme anxiety over the incident and was constantly on high alert. Fearing retaliation from the victim’s family, he moved his own family out of their home for two weeks.

In March 2001 his doctor put him off work again and told him she felt he suffered from PTSD.

What followed was counselling, medications, attempts to go back to work, applying for workers compensation and filling out forms that weren’t designed for dealing with a workplace mental health issue.

After his second attempt to return to work in 2006 Peckford was dealt a devastating blow.

He was told the force could no longer accommodate him. He had aspirations of progressing through the ranks, but now that was all gone.

“There was no longer a place for me in the organization.”

In 2010 Peckford was getting set to go to university when a change occurred at the RNC. Bob Johnston was named chief and Cal Barrett, commander of the Corner Brook and Labrador West divisions, was eager to get Peckford back to work. Barrett spoke with Johnston about Peckford. Finally there was some interest and effort to get him working.

It took eight months before that would happen.

He still struggles with his disorder, but now knows when to distance himself from situations and has flexibility in his work day to take time to address issues.

Looking back, Peckford said if the RNC had been doing more to address mental health issues from 1990 on then his situation may not have ended up where it was in 2001.

“But regards to 2001, could anything have been done different, I think it was too late at that point. The injury was there.”

Something that has changed for the better is the force’s protocol following critical incidents.

Now it is mandatory for officers to participate in critical incident stress debriefings. These have nothing to do with how an incident unfolded or was handled, but are all about the officer and how he or she is feeling.

Peckford has also become an advocate for mental health by sending out emails to other staff with information and tips to handling stress.

He spoke about his experience Thursday in hopes that it can do some good to help others, and to open the eyes of employers and encourage them to do more.

“Just because someone has a mental health issue doesn’t mean that it’s the kiss of death and that they’re no longer a valuable employee,” said Peckford.

“There’s no shame in having a mental health issue, just like there’s no shame in having a physical health issue.”